This summer, I got the chance to visit Stanford University in Palo Alto, Calif., on a college visit. Stanford, being one of the premier academic institutions in the United States, was of course, impressive. But to me, there was something that made Stanford stand out more than any of the other selective schools I have visited. The way Stanford approaches academics is something that I haven’t seen anywhere else and could redefine how academic studies are conducted in the future. But before I can explain that, I need to explain a little bit of history.

The blueprint that most American school systems follow today is nearly 100 years old. There has been some modification over the years as technology has advanced and the labor force has changed, but the core of our education system can be traced to William Wirt, who was the superintendent of Gary Public Schools in Indiana in the early 1910s. Wirt’s system, the Gary Plan, would deemphasize liberal arts education and instead focus on training students for the labor force from an early age. Young boys were taught vocational skills that would allow them to get assembly-line jobs at one of Gary’s many steel mills. Young girls were taught to be wives and homemakers.

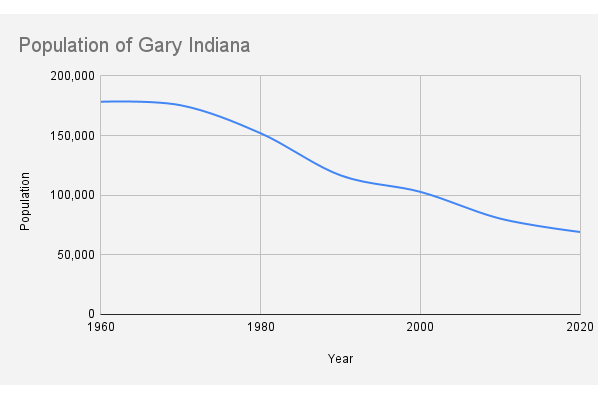

For the time, this was an effective plan. In the pre-digital age, one income could support a family and factory jobs were easy to come by, but that just isn’t the case anymore. Just look at what happened to Gary. The steel mills which caused the town to prosper closed in the 1970s and 80s as steel production was moved overseas. Gary is now one of the most neglected cities in the United States, and its school district, which once was home to over 50 school buildings, has seen a massive exodus of students and currently operates just nine schools. Building a school system around training students for an obsolete skill has caused this once-thriving district to wither. Yet, for most school districts around the country, including Millard, a variation of the Gary Plan serves as the basis for educating young minds.

This method of education, one that focuses on training kids for standardized tests that fail to measure student’s actual learning, one that keeps kids in school for long hours whether there is enough work to fill that time or not, and then assigns homework on top of that, one that forces students to conform to expectations that may not fit their goals, is an obsolete relic of the Industrial era. That’s where Stanford comes in. At Stanford, classes are centered around student learning, rather than test scores or statistics. Stanford allows their students to learn in a style that is comfortable to them, take classes that revolve around their schedule, and explore topics that interest them, whether they’re offered as classes or not.

But, Stanford has far fewer students than Millard does, and a greater pool of resources. How are we supposed to copy this model with the limited funding that we have while still preparing kids for life outside of high school? The answer is simple. Millard needs to offer even more blended classes. I am currently in blended college writing. I come to school when the teacher needs to give a lecture or check my work. All other work for the class is done online, on my own time. Because of my busy schedule, this is so helpful for me, and it has allowed me to excel in the class and really put my heart and soul into my writing. Millard needs to keep adding to the list of blended classes that already includes: college writing, college algebra, government, psychology, and marketing. There are plenty more that could be switched to a blended mode, and so many busy students like me who would love to have their schoolwork revolve around their life, rather than have their life revolve around their schoolwork. These classes could be offered alongside their regular counterparts to allow the students who benefit from the structure of the school day to succeed as well.

And in a weird twist of fate, a learning system centered on remote work would prepare students for the contemporary job market the same way the Gary Plan prepared students in the 1920s for a job in the steel mill. Most professions have moved a lot of their positions to remote work following the COVID-19 pandemic. The corporate office is going extinct in the same way the factory did 50 years ago. By training students with classes that mimic what they can expect to see in college and in the workforce, we can train them for life ahead while still working around their needs. Maybe this is the fix that America’s resented public-school system needs to adapt to the 21st century. No matter what, it is clear that the current system doesn’t work and should join the Model T Ford and the assembly line in the history books.