Critical Race Theory: What should be taught in the classroom?

Editorial

The beginning of March marks the end of Black History Month. But the month’s end doesn’t mean that the discussions and lessons on black history have to. This is the time to reflect, and the political climate over recent years makes that especially so. There are always criticisms to levy against how schools handle race issues in history classes, and now that the term critical race theory (CRT) has become a buzzword, there is a concerning amount of pushback against the teaching of historical lessons. The pushback has reached a tipping point, with bills such as SB3 in Texas, which targets social studies classes, and HF802 in Iowa, which targets inclusion training programs. Anti-CRT bills are being pushed by legislators across the country and should be stopped.

A research article published with the Brookings Institute in November 2021 found that Fox News had said “critical race theory” 1,300 times in four months. And nine states (Idaho, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina, Arizona, and North Dakota) passed legislation against it. None of the state bills, except for North Dakota and Idaho, explicitly mention the words “critical race theory” but every bill targeted concepts that are associated with it.

And even before this legislation, America’s troubling history with race already made it hard to teach in schools, because while most Americans can acknowledge that racism is bad, they can’t agree on how to present that to students. Those writing state standards can’t agree on how sympathetic the South should be portrayed when discussing the Civil War, nor can they agree on how to tackle topics such as white flight. This can be seen manifesting in textbooks, which have partisan bias, often in accordance with the different values of California and Texas, the two largest markets for textbooks. America has one history, but when the goal is to translate that into stories for students, there are many ways that one could go about that. Take this sample provided by the New York Times:

“Reasons for suburban growth varied. Some people wished to escape the crime and congestion of the city. Movement of some white Americans from cities to the suburbs was driven by a desire to get away from more culturally diverse neighborhoods…” This is what the relatively left-leaning McGraw-Hill US history textbooks of California have to say about white flight. Contrast this with the Texan version of the publisher’s history textbook, which only says: “Reasons for suburban growth varied. Some people wished to escape the crime and congestion of the city…” And then proceeds to talk about how government policy made homeownership “more attractive than ever” in stark contrast to the Californian book which at that point elaborated on the institutional discrimination faced by black people, which left the suburbs as completely segregated white havens.

The GI Bill and tax deductions did make home ownership more affordable, but only for white Americans, many of whom were also driven to the suburbs by the desire to distance themselves from people of color. Both can be correct. But when the topic is white flight, downplaying or omitting the role that racism played is a lie by omission, and is driven by the desire to distance curriculums from what has come to be considered critical race theory.

There are two fronts that the war against critical race theory is being fought on. There’s the debate about whether or not teaching CRT is a good thing, and there’s the debate about whether or not CRT is being taught in k-12 schools at all. That’s why it’s important to take a look at the five core tenets of critical race theory.

The tenets are ideas such as that racism is ordinary and not aberrational, which dispels the notion that racism is an outside threat to society rather than an intrinsic one. It contains the idea that race is socially constructed and defined in ways that hurt people of color, like the arbitrary one drop rule. Critical race theory is the idea that “storytelling” is used in schools in ways that primarily serve white students by elevating white stories and structuring curriculum on white middle-class values and advocates for “counter-storytelling” to share the experiences, stories, and narratives of the historically underserved. Critical race theory demonstrates that in many instances, white Americans have been the recipients of civil rights legislation, such as when the ruling of Brown v the Board of Education led to minority students being left behind as those who could afford it white-flew their way out of those areas.

In short, it’s the acknowledgment that systemic racism exists and that the legacies of slavery and segregation haven’t disappeared. By these standards, it’s hard to see where critical race theory is taught in schools, since in most schools, civil rights units are taught on a surface level in history classes as opposed to sociology classes that would explore modern impacts.

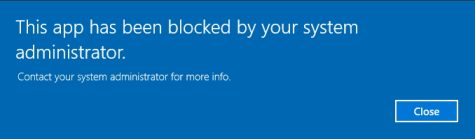

Bill 1077 is working its way through the Nebraska legislature. The Government, Military and Veterans Affairs Committee heard three hours of testimony Feb. 24, but no action was taken. The bill is nearly identical to the one that has already passed in Iowa. In July 2021, Iowa passed bill H.F. 802 “that prohibits state government, local government, community colleges, K-12 schools, and regent institutions from providing any mandatory training to employees or students that teaches, advocates, acts upon, or promotes divisive concepts.” Iowa governor, Kim Reynolds, explicitly said that she wanted to target “critical race theory indoctrination” when she signed it. The bill isn’t all bad, but the trouble comes with the way that it defines “divisive concepts.” It bans the teaching that an individual is inherently oppressive based on their race or sex, which is understandable. In fact, critical race theory never proposes such an idea in any of its tenets. But the bill also stops the training from teaching that “Iowa or the United States is fundamentally racist or sexist…” Replace “Iowa” with “Nebraska” and that exact line is also in LB1077. Which prohibits a vital part of inclusion training: the acknowledgment that things aren’t okay. An important part of being conscious of discrimination is being able to acknowledge that it isn’t just the malice of a few bad people, but is also present in the roots of our society. That is in line with the tenets of critical race theory, and it’s correct.

Instead of legislating to cover up the biggest flaws in our country, we should be actively endorsing the discussion of these problems and their solutions. Those of us who advocate for the teaching of systemic discrimination, past and present, are being put into a position where we have to defend the alleged “critical race theory” already in the curriculum. But there isn’t a good case that critical race theory is in schools at all, though maybe it should be if that’s the best avenue to properly teaching about systemic issues and the legacies of the past. The true threat to our education isn’t critical race theory, it’s the war that has been waged against the strawman of what politicians are calling critical race theory.

Like what you see here? Your donation will support the student journalists of Millard South High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase cover most of our annual website hosting costs.

Darian Pierre is a Senior at Millard South high school, and this is his first year on the Newspaper Staff. He likes computers, animals, and art. He is...

Rebecca • Mar 4, 2022 at 8:03 pm

Wonderful, informative article, Darian!